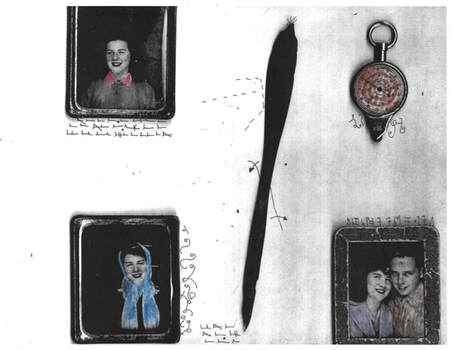

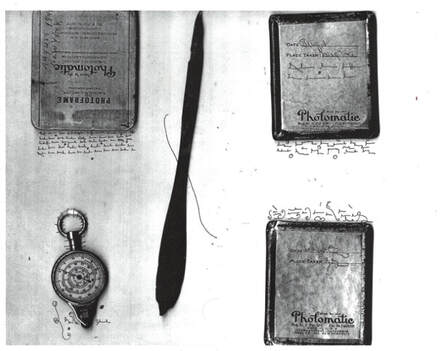

Family is a Tower of Babel 1 & 2, Nadia Arioli, 2023. Scan of photographs, letter opener, and compass, modified with colored pencils and pen.

Time Keepers

Ann Iverson

My mother used to collect antique 18 jewel Swiss watches. She discovered that the more she wore them, the better they ran, so she wore them round the clock, sometimes three or four at a time. When she passed, the nurse handed me a plastic bag with three watches in it and said, “Your mother was wearing three watches.” I could tell by the curious look on her face that she thought that to be so odd. But it was just my mother, collector of all things, fixer of things that didn’t work, master of old things and things that are fragile.

In the basement she refurbished enormous antique hutches, frames, mirrors, chairs, and the like with no caution for the fumes. At any given moment, the house smelled of turpentine, paint remover, and linseed oil; but even more than that it smelled of imagination and whimsey. She moved within her creativity as any artist does, from one idea to the next in a restless attempt at beauty: sewing curtains, slip covers, pillows; stringing beads; hanging art, moving it and hanging it again, and rearranging furniture. It seemed that every week the French Provincial sofa was someplace new; one time she even put it in the kitchen. But mostly for me the house smelled of love: on Sundays, pot roast and potatoes after church on the long harvest table; on Easter fancy dresses and shiny shoes, pictures at the Conservatory, on Christmas, potato chips and French onion dip, and Dad bellowing out, “Ho, Ho, Ho,” from the bedroom. She checked her lists and checked them twice, she paid the bills, she scrubbed the floors and made us pray. She told us that Jesus was our best friend.

It comes with such ease to remember her as the artist sitting at the kitchen table shining brass brooches or dying leather purses, looking out the window, watching the neighbor’s dog, saying how she wished they’d let him out of his kennel more because all he does is pace, then reminding me not to feed my dog chocolate for the rare chance of canine heart failure, though she never mentioned her own weakened heart. On a quiet winter morning she died in her sleep with three watches on her wrist.

My father, on the other hand, always kept the kitchen stove clock set ten minutes ahead. From the bedroom, he’d call out, “Hey, Baby, what time is it out there?” As a teenager, I sarcastically thought, I don't know? Ten minutes later than it is in there. But over the years I became accustomed to, reliant on, that psychological cushion of I’ve still got time, keeping me ten minutes ahead of every heartbreak to come, every joy to blossom, every quiet neutral day of life.

My dad--Jack, as most people called him--was as naturally himself as a person could be, no pretense, no fluff, no filler. He used socks for gloves, wore the same tan jacket for years, and mowed the grass with a push mower. The year that our mother passed, we bought him a microwave for his birthday though he refused it. When he was four, his father passed from pneumonia. For financial reasons, he left school after the eighth grade, but he was self-taught and well-read. When my mother’s health began to decline, he cared for her with great bravery. No classroom can teach that. No classroom could have taught my dad how to live in a one bathroom, three-bedroom house with six women. And he too always wore a wristwatch--not three, just one with a dead battery.

You either love your parents for what they are, or you don't. While we live, we die, and when we die, we live. There is nothing in-between. We are either here, or we are there. And since there is no one here to argue this point. I think my parents loved each other, and their love was very much like a long symphony in which I’ll never understand the meaning behind the great and forceful gestures or the restless abundance of song or the cacophony and the sorrow and the accord which finally comes in old companionship. Yes, to only those who’ve had their fill.

Ann Iverson is a writer and artist. She is the author of five poetry collections: Come Now to the Window by the Laurel Poetry Collective, Definite Space and Art Lessons by Holy Cow! Press; Mouth of Summer and No Feeling is Final by Kelsay Books. She is a graduate of both the MALS and the MFA programs at Hamline University. Her poems have appeared in a wide variety of journals and venues including six features on the Writer’s Almanac. Her poem “Plenitude” was set to a choral arrangement by composer Kurt Knecht. She is also the author and illustrator of two children's books. As a visual artist, she enjoys the integrated relationship between visual and written images. Her artwork has been featured in several art exhibits as well as in a permanent installation at the University of Minnesota Amplatz Children’s Hospital. She is currently working on her sixth collection of poetry, a book of children’s verse, and a collection of personal essays, Then Eat My Love, forthcoming from Southern Arizona Press.