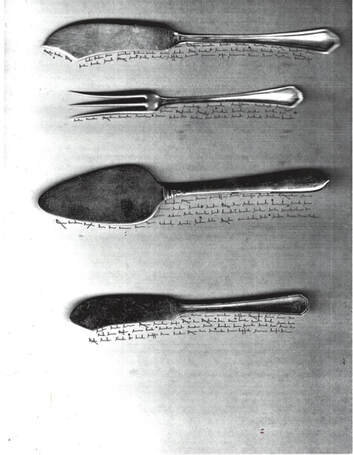

Pageantry 1 & 2, Nadia Arioli, 2023. Scan of utensils, modified with colored pencils and pen.

What Grows together goes together

Amy Cotler

Our Baby Carrot. When we picked Emma up on that first day, in the hospital in Springfield, Tennessee, she was not as expected. Newborns can have misshapen heads from the push, we were told. And their facial features may not be settled yet. In short, they’re ugly.

We opened the door and edged closer, where we could see her tall body with the long fingers of a Balinese dancer. How could she be ugly?

A large nurse in a pert cap handed me our new daughter, and sat me in a rocking chair in the nursery. My husband, Tommy stood above me at a respectful distance. “What do you think?”, I asked, looking down nervously at our baby.

“What’s not to love?” answered the man who, up until a few months before, wasn’t sure whether he even liked children.

A Carrot is a Carrot. No, she wasn’t what we expected. I’d envisioned a malleable lump, someone we could model and form. Anything was possible. Not so. Odd, but, as a working chef, I soon began to see our baby as closer to an ingredient—say, a carrot—which will always be a carrot, however malleable. If nurtured, carrots grow well. Left untended, without peat and compost, my soil was so dense you could squeeze it into a ball that would hold. Carrots like low-acid, loamy soil with good drainage, so they can grow straight down. Breathe and wiggle their pointy ends. So I amended my soil just for them. But in any soil at all they would have grown into carrots, sick or well—gnarly and bitter or sweet and crunchy. You can’t pull them up and turn them into broccoli or kale any more than Emma can become someone else—shorter, more talkative, not drawn to animals of all kinds. And carrots will never taste green, though God knows some genetic engineer may try one day.

Both Emma and carrots are dependent on the environment in which they grow and the genes within, cultivation and cultivar, nurture and nature. Certainly, reading Flat Henry or A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, while cuddled together in Emma’s bed, helped her grow into her healthiest self. (Of course, eating carrot-ginger soup didn’t hurt either.)

I suppose her DNA mandated that she stare dreamily up at the moon, out the window, above her attic bed in a manner that was totally Emma. She established roots in her bed, as my carrots did in theirs, just outside the very same house where she lay, distinguishing themselves by their variety too—broad shouldered, multicolored, or long and thin, as Emma was. Still, like most moms, especially adoptive moms, I worried. Then one night, driving home, her tiny voice rose from the car seat behind me, “Why does the moon follow us home?”

Ordinary in her way, a little girl growing up in an old house in the country. But unique already. She may have been a little American girl, who fit in visually with the preschool crowd. But she never toddled with the pack. Only two years later she’d draw ornate mermaids that her classmates colored in. This new person, born her particular cultivar, was an observer, unlike anyone else in our family, growing into herself, with a little nourishment from us.

Our Garden. What grows together goes together. That went for my new family and my vegetable garden too. There, companion plants grew side by side, enriching each other’s happiness while keeping harmful bugs away. With a little help from a friend, nature’s alchemy makes the best chef. Simmer eggplant, tomatoes and zucchini that ripen together in their season into a ratatouille. Toss fresh herb sprigs snipped at the same time into a summer salad. And so my husband, daughter and I mingled too, not in a pot or bowl, but in our ramshackle home in the middle of nowhere.

When Emma was a toddler, we walked out by our New England barn with its wavy windows that tilted to one side. Behind it lay a seasonal stream that edged our property. Come spring, it was spotted with tangy watercress, rising up a few inches above its surface. By summer, we borrowed a rototiller from Bub, the handy farmer who lived across the street. Being city folk, my husband, Tommy, and I looked out at a green expanse we didn’t recognize. Who knew it was filled with burdock and lamb’s ear and clover? We just saw weeds. As we turned over our soil, we dug up bits of blue and white crockery, a few rusty horseshoes, even a broken gravestone with a morbid epitaph on it, probably rejected from the cemetery across the street.

Emma toddled out to our new garden, her tiny hands curled around mine. With one finger each, we pressed a line of indentations into the soft soil. Then we dropped a pea seed into each hole—sugar snaps planted next to feathery dill, to be tossed together with butter. Later that summer, in our kitchen, around the time our snaps could be harvested, we lifted Emma in our arms together, Tommy and I. Swinging her gently side to side, we sang “Rock Around the Clock,” an act that gave us all comfort when one of us was cranky, or life felt out of skew.

By late summer, I’d lay just-picked rosemary on the kitchen counter, perfuming the kitchen with its piney scent as we rocked her. As Emma grew drowsy, Tommy tiptoed her up our narrow stairs to bed. When he didn’t come back, I knew he’d fallen asleep too. I’d stand in the kitchen, breaking up the rosemary stems, then pressing them into a large glass jar filled with salt. The salt would dry out the rosemary, so I’d have rosemary salt to cook with later that winter. And while it’s true that salt and rosemary don’t grow together in any manner whatsoever, I’m not rigid about what belongs. Proximity creates intimacy, in people and ingredients both.

Amy Cotler was a leader in the farm-to-table movement, and a food forum host for The New York Times. After her career as a food writer and cookbook author, she turned to creative writing. Her short pieces have appeared in various publications, including Guesthouse and Hinterland. Cotler lives in central Mexico. For more, visit: www.amycotler.com. For samples of her published work: http://www.amycotler.com/offerings/